Adapted from the article, Mindfulness for Social and Emotional Competence: A Review of the Research by Jillian Haydicky, Ph.D., & Judith Wiener, Ph.D.

Does your child ever have a big emotional reaction to something that seems minor, like completing their homework or an upcoming test? Maybe they act out or come up with excuses to avoid starting their work. These can all be signs that your child is experiencing stress.

Everyone experiences stress from time to time. It is a natural reaction to certain events in our lives, such as demands at work or at school, uncertainty around change, or difficult social situations. Stress typically does not last very long or affect our day-to-day functioning. But some people experience longer periods of heightened stress.

Children and youth with learning disabilities (LDs) typically experience repeated failure. In school, they may work incredibly hard but the outcome may not reflect their effort. This can all lead to the experience of negative feelings, including worry, anger, frustration, and sadness. When it is hard to ‘show what you know’, it is understandable that we might see higher rates of school-related stress and anxiety. Individuals with LDs are two to three times more likely to experience a variety of mental health challenges (Wilson et al., 2009). Additionally, it is estimated that 75% of children and youth with LDs face challenges with social relationships (Kavale & Forness, 1996) and they are more likely to report peer victimization and bullying (Baumeister, Storch & Geffken 2008; Mishna, 2003).

To learn more about the connection between learning disabilities and mental health, click here at access LDMH: A Handbook on Learning Disabilities and Mental Health, created by the Integra Program at the Child Development Institute.

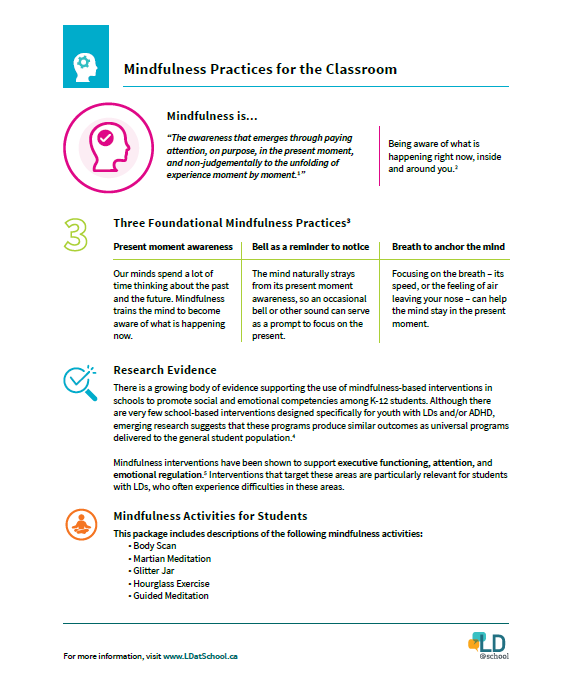

It is clear that, along with academic difficulties, students with LDs face more social and psychological challenges than their peers. Students with LDs need to be taught coping mechanisms before stress, social isolation, or negative emotions can take a toll on their well-being. Thankfully, there is a growing body of evidence supporting the use of mindfulness-based interventions in schools to promote social and emotional competencies among K-12 students.

What is Mindfulness?

“Mindfulness is the awareness of what is happening inside and around us in the present moment” – Plum Village Community, a global mindfulness community, founded by zen master Thich Nhat Hanh.

“Mindfulness means paying attention in a particular way; on purpose, in the present moment, and non-judgmentally” – Jon Kabat-Zinn, Mindful Base Stress Reduction (MBSR).

In the definitions above there are a few key terms that are essential to the theory of mindfulness:

Awareness

Awareness is simply being aware of what’s happening. Awareness is a word that we all are very familiar with, yet much of our days are spent not being aware. How often in a day do you lose the awareness that you have a body, and realize several hours later you need water, you need to go to the bathroom, or you haven’t taken care of yourself?

Awareness is also directly connected to attention. Attention impacts our ability to take in new information and learn.

The Present Moment

Mindfulness is not awareness of the future, which can lead to the mind becoming overwhelmed with worries and anxiety. Similarly, mindfulness is not awareness of the past, which can lead your mind to replay past events and relive negative emotions.

Learning only happens in the present moment. Learning is what is in front of us right now. Teaching students to become aware of the present moment is an incredibly useful skill both for learning math and also for handling strong emotions.

Click here to learn how to identify and support students who experience anxiety.

Non-Judgement

Non-judgement refers to both not judging others as well as not judging yourself. To not judge yourself or compare yourself to others is an incredibly difficult and powerful thing to do, especially for students with LDs, who may regularly fall behind their peers. Anxiety and fear often arise from our own perceptions and judgments of a situation, both towards ourselves and others. Self-judgement can impact students’ social-emotional development, cognition, and their ability to use executive functions.

Common elements of mindfulness-based programs include:

- guided breathing practices

- mindful movement such as yoga to promote body awareness

- kindness and compassion exercises

- activities to increase awareness of thoughts, feelings, and how the mind works

The benefits of Mindfulness for Students with LDs

In times of stress or perceived threat our bodies naturally react by going into fight (reacting with aggression), flight (running away from the threat), or freeze. This happens even if the threat is not life-threatening, such as anticipating an exam or giving a public speech. The stressed mind is too focussed on trying to keep you alive to pay attention, think clearly, control emotions, or learn. If the source of your stress is your learning challenges, as it often is for students with LDs, it becomes clear how stress can turn into a seemingly never-ending cycle. Regularly practicing mindfulness can help students learn to recognize the signs that they are becoming stressed and gives them strategies to come back to a state of calm.

Research has shown that using mindfulness activities with students with LDs has lead to improvements in:

- physiological, psychological, and behavioural functioning (Black et al., 2009)

- executive function skills, including behavioural regulation and metacognition, or the ability of students to think about and understand their own thinking (Flook et al., 2010)

- attention skills (Napoli et al., 2005)

- emotion regulation (Mendelson et al., 2010)

- social skills (Beauchemin et al, 2008)

- academic performance (Beauchemin et al, 2008)

Mindfulness has also been shown to lead to reductions in:

- the physical signs of stress, such as raised blood pressure and heart rate (Barnes et al., 2004)

- anxiety (Beauchemin et al., 2008; Semple et al., 2010; Smith-Carrier & Gallinaro, 2013)

- depression (Joyce et al., 2010; Kuyken et al., 2013)

- externalised behaviours, oppositional and behavioural difficulties (Haydicky et al., 2012)

How to do Mindfulness at Home

Many school boards throughout Ontario and across Canada have adopted mindfulness programs. You can use the same principles to help your child lower their stress and improve their executive function, attention, and emotional control at home.

The LD@school team has compiled a guide of 5 mindfulness activities from resources across our website that can be easily adapted to the home. Click here to access the guide Mindfulness Practices for the Classroom.

References:

Baumeister, E. A., Storch, E. & Geffken, G. (2008). Peer Victimization in Children with Learning Disabilities. (Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal) 25:11–23

Barnes, V.A., Davis, H.C., Murzynowski, J.B., & Treiber, F.A. (2004). Impact of meditation on resting and ambulatory blood pressure and heart rate in youth. Psychosomatic medicine, 66(6), 909-914.

Beauchemin, J., Hutchkins, T.L., & Patterson, F. (2008). Mindfulness meditation may lessen anxiety, promote social skills, and improve academic performance among adolescents with learning disabilities. Complementary Health Practice Review, 13, 34-45. doi: 10.1177/1533210107311624

Black, D. S., Milam, J., & Sussman, S. (2009). Sitting-meditation interventions among youth: A review of treatment efficacy. Pediatrics, 124, e532–e541. doi:10.1542/peds.2008-3434

Flook, L., Smalley, S.L., Kitil, M.J., Galla, B,M., Kaiser-Greenland, S., et al. (2010). Effects of mindful awareness practices on executive function in elementary school children. Journal of Applied School Psychology, 26, 70-95. doi: DOI: 10.1080/15377900903379125

Haydicky, Shecter, Wiener, & Ducharme (2013). Evaluation of MBCT for adolescents with ADHD and their parents: Impact on individual and family functioning. Journal of Child and Family Studies. Advance online publication. doi:10.1007/s10826-013-9815-1

Joyce, A., Etty-Leal, J., Zazryn, T., Hamilton, A., & Hassed, C. (2010). Exploring a mindfulness meditation program on the mental health of upper primary children: A pilot study. Advances in School Mental Health Promotion, 3(2), 17-25. doi: 10.1080/1754730X.2010.9715677

Kavale, K. & Forness, S. (1996). Social skills deficits and learning disabilities: A meta-analysis. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 29 (3), 226-237.

Kuyken, W., et al. (2013). Effectiveness of the Mindfulness in Schools Programme: Non-randomised controlled feasibility study. British Journal of Psychiatry. Published online in advance of print. Retrieved from http://bjp.rcpsych.org/

Mendelson, T., Greenberg, M.T., Dariotis, J.K., Gould, L.F., Rhoades, B.L., & Leaf, P.J. (2010). Feasibility and preliminary outcomes of a school-based mindfulness intervention for urban youth. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 38, 985-994. doi: 10.1007/s10802-010-9418-x

Mishna, F. (2003). Learning disabilities and bullying: Double jeopardy. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 36, 336-348.

Napoli, M., Krech, P.R., & Holley, L.C. (2005). Mindfulness training for elementary school students: The Attention Academy. Journal of Applied School Psychology, 21, 99-125. doi: 10.1300/J008v2n01_05

Semple, R.J., Lee, J., Rosa, D., & Miller, L.F. (2010). A randomized trial of mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for children: Promoting mindful attention to enhance social-emotional resiliency in children. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 19, 218-229. doi: 10.1007/s10826-009-9301-y

Smith-Carrier, T., & Gallinaro, A. (2013). Putting your mind at ease: Finding from the Mindfulness Ambassador Council in Toronto area schools. Toronto, ON: Factor-Inwentash Faculty of Social Work, University of Toronto.

Wilson, A. M., Deri Armstrong, C., Furrie, A., et Walcot, E. (2009). The mental health of Canadians with self-reported learning disabilities. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 42(1), 24-40.